Author: alcalareview

A Descent in Early Spring – Owen Clarke

This piece of creative nonfiction by Owen Clarke is selected from our upcoming Fall 2018 Issue. The full issue will be released and available for purchase here and at our Publishing Party on December 13.

a descent in early spring

by

owen clarke

The stone refuge was nestled below the top of the pass. We were huddled inside around the woodstove, prepping our packs for the descent, when the porter stepped inside. The howl of the wind echoed briefly through the refuge as he opened and shut the door. He was still wearing his crampons and he didn’t bother kicking the snow off his boots. Something was wrong. The guides and porters got to their feet. The one who’d entered spoke a few lines in Berber. The men spoke briefly. The porter was raising his voice.

“What’s he saying?” I asked Hassan, my Berber guide.

Hassan grunted. “A man fallen.”

Hassan didn’t speak often. He knew little English, but I had a feeling he was reticent even among his fellow Berbers.

“Someone fell?”

He nodded. “Yes.”

Hassan stood a few steps back from the cluster of porters and guides. His arms were crossed, his eyes hard.

I grimaced. I wondered who it was. There had been around forty people in the refuge the previous night, most attempting the summit in the morning. After a 3:00 a.m. start, Hassan and I had reached it early, around 8:00, under winds that had to have been at least sixty miles per hour. We were the first party down from the summit. Visibility was barely ten feet during our descent, and the storm was only growing. It took us a few hours to get back to the refuge, and we’d only been back for a few minutes when the porter arrived.

The Berbers were strapping on crampons, stuffing packs with first aid supplies.

“Are you going with them?” I asked Hassan. “Is there anything I can do to help? I’m an EMT.”

Hassan shrugged noncommittally and said nothing. He tossed an ice axe to Akhmed, our muleteer. I went back inside and sipped mint tea around the wood stove with two Canadians, a father and son, who hadn’t made the summit. The kid had gotten lightheaded at 12,000 feet, his dad told me, which is when they had turned back.

“Probably it’s like fate or something, that I got a bit sick, you know?” the kid said. “I mean, that guy could definitely be dead, right?”

“He definitely could,” said the father. He turned to one of the Berber guides walking by. “Can they not get a helicopter up to him?”

“No helicopter. Winds too strong,” the Berber said. “We bring him down on litter to refuge, then to Imlil on the mules.”

A few minutes later, Hassan came back inside, kicking snow off his boots.

“Akhmed go with men,” he said. “We carry things down. You. Me. No mule.”

“We’re going down? Don’t you need to go with them to help? I’m fine staying here at the refuge. Or I could go too.”

“Enough men go,” said Hassan, shaking his head. “Need be in Marrakech tonight, no?”

My train left for Tangier at seven.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Get things,” said Hassan. “We go.”

We stuffed our packs with Akhmed’s supplies. Afterwards, we left the refuge behind, the Canadian kid staring balefully after us through the frosted glass windows. There was still snow for the next couple of miles, but it was soft, sparse, and shallow at this altitude, and the postholes were clear, so we left our crampons off.

We came down through the valley, Hassan ranging far ahead. When we stopped for water at the snowline a couple of hours later, he left to scour the hillside for our mule, which Akhmed had tethered the day before.

I sat on the edge of the snowline. I’d come because Toubkal was the highest peak in North Africa and the Arab World, though it sat at a relatively measly 4,000 meters. I was in Marrakech tagging along with my friend, a poker player, who was playing tournaments there, when I’d realized Jebel Toubkal was only a couple hours to the south. It’s known as a relatively easy peak, a total walk-up in the summer, and not much more than a walk-up with crampons and a glacier axe in the winter. So I figured, who wouldn’t go for it, with such little risk? I’d even gone so far as to hire a guide, what with travelling alone (my friend would stay in Marrakech) and having brought no ice gear along with me.

In summer it was a walk-up, and winter, as per usual, necessitated the typical tenfold increase in caution. Here we were, on the cusp of spring, and someone had fallen. Clearly badly, or the porters wouldn’t have mobilized like they had. It wasn’t that I didn’t think it possible, it had definitely been a fairly harrowing ascent with the wind. But I had never really considered serious injury on a peak like this.

Hassan returned, shaking his head. “Mule gone,” he said, spitting into the dirt.

“You said weren’t gonna use him anyway, right?”

He frowned at me. My sentence must’ve been too long.

“Mule gone,” he said again.

He rubbed his weathered face. Several dilapidated huts were clustered around the trail at the snowline. Hassan spoke to a man squatting in a doorway. He ducked inside and came back with two glasses of mint tea. We sat on a low stone wall on the side of the trail, sipping our tea and looking down into the valley.

“Man no speak,” said Hassan. He gestured inside the hut. “Hear on radio from Mohammed.”

“He’s not speaking?”

Hassan nodded. “Eyes no open.”

“But he’s alive?”

Hassan shrugged. I assumed this meant yes.

“Do they know who he is?”

Hassan frowned. “English…think, maybe, you eat with? In the night?”

I had eaten dinner with an English couple the night before at the refuge. They were from Exeter. The man was a software developer. They had offered me a seat at their table, given me some of their soup.

“The people I ate dinner with? The man and the woman? Kinda tall? Glasses?”

“Think,” said Hassan. “But not know. Radio say one English fallen, of two. So…maybe you eat with?”

There weren’t any other Brits at the refuge going for the summit. I had talked to the guy and his wife earlier that day. They’d only been a hundred yards from the summit when we’d passed them on our way down. They were the party closest behind us. It must have been them. It felt strange, knowing an accident had happened only moments after I’d passed them. We would have heard it if hadn’t been for the wind. The man was young, maybe 30 at the oldest. He was newly married.

“Is he going to be okay?”

Hassan shrugged.

“Can they really not get a helicopter up there? One of the men said the winds were too strong. You think they’ve eased up by now?”

Hassan looked down for a moment. I wasn’t sure if he was translating what I had said or trying to think of what to say himself.

He looked back at me. “Not too many wind. Helicopter not come because too many wind. No money, helicopter not come.”

“If they can’t pay, they won’t call the chopper?”

“Yes.”

We sat in silence. I finished my tea. Several mules dotted the hillside below us, sloping down to the stream at the bottom, which ran down towards Chamharouch. I thought of the British couple, the young man, not much older than I. Neither were experienced climbers, but you didn’t need to be for a peak like this. Or maybe you did, but sometimes it didn’t matter. It was a testament to the inherent chaos always present in the mountains.

They’d talked about having kids. They told me they wanted a boy.

I turned to Hassan.

“Do you have any family? Kids?” I asked.

“Girl,” he said. “Three girl. One seven year. One three year. One sixteen day.”

“You have a baby girl? Sixteen days old?”

Hassan nodded. For the first time in the days I had travelled with him, he smiled. He rummaged in his jacket pocket for a minute, then pulled out a folded photo. He showed it to me. A baby was wrapped in blankets, grimacing under the lens flash of a camera.

“This is your daughter?”

“This is why I come to mountains. Make money as guide.” He paused. “This is life.”

He folded the photo up and slipped it back into his jacket. We finished our tea.

“We go,” he said.

We followed the valley downwards, keeping the mountain stream on our right. At this altitude, the winds had softened. Looking back through blue skies towards the summit, just out of sight behind the smaller peaks to its north, it was hard to imagine what was going on only a few thousand feet higher. The winds whipping through the slopes and along the rocky ridgelines, tearing off fragments of snow and ice and propelling them through the air at hellish speeds. I almost forgot that I’d been in the midst of that only this morning. Somewhere up there, a man was being drug out on a litter. The Berbers were calling to each other over the sound of the driving wind. The snow was softening and crampons were starting to lose their grip. The Englishman’s wife was following behind the litter, clutching his hands, her eyes frantic. Perhaps they’d made it to the refuge. I did not know and Hassan, it seemed, did not care. From here, at least, all looked well. The mountain was quiet.

* * *

Large black birds soared through the sky above us, spiraling downwards through the valley. Patches of snow still dotted the hillsides, but we were below 10,000 feet now and most of the snow had melted. We passed two parties on the ascent, one of French climbers and the other Moroccans. Hassan did not speak to them.

Sidi Chamharouch was peaceful when we arrived. There were a few parties of climbers, eating at a handful of small cafés, and Berbers milled among the huts. Men in djellabas herded shaggy, black goats along the rocky slopes. We stopped at a café high on the mountainside above the village. Hassan left to prepare the food. I sat on the terrace opposite a large, balding white man with a thick beard.

“Speak English?” he grunted. I heard an accent, but couldn’t place it. Something European. Harsh. Norwegian, maybe.

“Yeah,” I said.

“Been up?”

“Yeah. You?”

“Up there last night. We slept in the same room at the refuge.”

“Oh…huh.”

My room was made up of twenty or so bunks, mostly populated with hairy Russians who snored like boars and were named Igor or Alex.

“I didn’t notice,” I said.

The man grunted something unintelligible.

We looked out over the town below, the trail leading down to the dry riverbed and Asni, then the mountain village of Imlil. The large, white rock of Chamarouch’s ancient shrine lay nestled in a crook of the hillside to the east, just across a small wooden bridge spanning a creek. This bridge was the boundary for outsiders. The shrine was forbidden to non-Muslims.

No one was entering the shrine. A man in a dusty brown djellaba leaned against the railing of the bridge, smoking a cigarette. The rock was festooned with brightly colored flags.

Tagine and bread was brought by a stunted, gap-toothed Berber wearing a skullcap and a leer. The face of the Englishman flashed into my head upon seeing the food. Phil. That was his name. Phil. I thought of dinner the night before. Listening to his stories about his only visit to the states. He’d scoffed at the increasing price of bitcoin, because he’d owned twenty a few years ago and sold at no profit. He and his wife had said they were going to Merzouga, to see the desert, after they summited Toubkal. So was I, eventually. I wondered if they’d make it there now.

“You summit?” I asked the man.

“No.”

He pulled up his pant leg, revealing a gash down his right calf. The top of his leather boot was torn a couple inches down, the outside of his pant leg shredded.

“Damn. What happened?”

“Yesterday,” he began, then paused, coughing violently. “I was taking photos on a ridge near the refuge, took a fall. Slid a hundred meters down the slope, almost to the edge of the cliff. Would’ve been dead if I’d gone over.” He laughed. “After that, I thought, maybe I won’t summit.”

He laughed again. It was a harsh, smoker’s laugh. “I’m too old to have anything to prove.”

I nodded. “Somebody took a bad fall up there today, too.”

“Mhmmm.”

Behind the man, Hassan was waving to me. “We go,” he called.

I stood up and grabbed my pack. “Safe travels,” I said.

The man coughed, nodded. “To you the same.”

* * *

Hassan tried to get a radio signal from the refuge before we left Sidi Chamharouch, but couldn’t get through. We travelled down the valley and into the wide, dry riverbed, littered with boulders and small streams like dying veins. On a cracked dirt field, a group of kids was playing soccer in the shadow of the mountains. Two policemen in dusty uniforms rose swaying on mules up the trail from the north, where the riverbed melted away. They lugged a large radio and called to Hassan in Arabic. He broke off to talk to them.

“Take break,” he said to me. “Take break.”

I squatted on a boulder at the side of the trail while Hassan gestured to the policemen. One eyed me warily, scratching his chin, as the other spoke to Hassan. After a few minutes, the policemen continued on their mules up the trail. Hassan came and sat by me on the boulder. I offered him some water.

He drank. “Him now black,” he said.

“Huh?”

“Him now black.” He passed a hand over his face, his eyes closed. “Black inside.”

“Dead?”

Hassan nodded. “Dead, yes. Police hear on radio. They go up. Take photos of body at refuge.”

“He’s dead?” I repeated.

Hassan nodded again.

It was strange. Somewhere inside I’d already known the man was dead, even before Hassan had told me. I just hadn’t been aware of it. As soon as we’d heard he’d fallen, I’d known. I could see his face when I’d passed him on the summit ridge. I’d spoken to him but he hadn’t responded. He had been pale and drawn. The altitude had been getting to him. Should I have said something? Asked if he was okay? Surely his wife and their guide had already noticed. I wondered how long it had been after I’d seen him until he’d fallen. It had to have been only a few minutes. They’d been so close to the summit when we passed. We likely would’ve seen it if the visibility hadn’t been so poor. I remembered the precipice to the south of the summit ridge, imagined a body flailing through the air.

But still, I hadn’t seen him die. I hadn’t even known him, really. A few hours of conversation over a meal was the extent of it. Why should I care? I’d had plenty of relatives die before, grandparents and the like, people I actually knew well, but this was different. This guy was young, and Toubkal was supposed to be a walk in the park, just a bit of glacier travel.

I heard the voice of the injured man from Chamharouch in my head. I’m too old to have anything to prove.

For a moment I thought, What the hell am I doing here?

“Maybe you no think, but many people dead on Toubkal,” Hassan said, reading my thoughts. He tossed me a bag of dried fruit. I picked out a date and ate it.

“People dead every year.” He drew a finger across his neck. “My father not want me climb Toubkal. Say money not worth life.” He paused. “My brother dead there. Like English.”

“He fell?”

Hassan ignored my question, and was quiet for a moment. “You die, lose life. Yes. But…” He patted his chest. “This not life.”

He pulled the photo of his baby daughter from his pocket again, pointing to it. “This is life. Outside you, is life. Need money for this life. So I climb. Guide.”

“You think it’s worth it?” I asked.

He shrugged. “You climb mountain…maybe you dead. Maybe you fall here, hit head,” he pointed to the dirt trail, “you dead. Maybe driving automobile… crash. Dead. Maybe you dead in sleep.” He paused, and we sat silently for a long time.

“Better dead on mountain,” Hassan finally said. “Closer.”

“Closer to what?”

He did not respond, and I did not press him further.

We sat on the boulder. The black birds floated through the sky. The kids on the dirt field in the distance kicked the soccer ball and yelled. A cluster of goats bleated from the hillside to the east. In Imlil below, Hassan’s newborn daughter waited for him. In Marrakech, my train was at the station.

Hassan popped a date into his mouth and chewed for a moment.

He spit out the pit. “This is life,” he said.

We continued down the trail.

Owen Clarke, 21, was raised in northern Alabama and began writing at the age of 11. His work has been published by magazines such as Rock & Ice, Gym Climber, and Trail Runner. He is a senior English major atUSD.

The Fall 2018 Issue (and Party)

The final edits of The Alcalá Review’s latest issue are done and at the printers.

Come and join us on Thursday, December 13th, at 7:00pm in Saloman Hall, to celebrate the release of our Fall 2018 issue. The event will feature a reading by the USD English department’s own Professor Melekian, catered food, and, of course, the first opportunity to buy the journal. (It’ll be available online here shortly after). All are welcome.

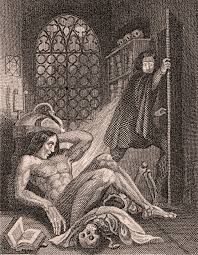

Frankenstein Bicentennial: Call for Scary Stories

In Brief: To commemorate the bicentennial of Frankenstein’s publication, The Alcalá Review is holding a scary short story contest.

Reflecting on the origin of her infamous Gothic novel in her late years, Mary Shelley recalls experiencing a classic case of writer’s block:

…I busied myself to think of a story —a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name (“Preface” to Frankenstein, 1831).

Born of a ghost story competition among a small group of friends during a rainy summer in 1816, Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus has certainly outgrown its modest beginnings. Two hundred years after its original publication in London in 1818, Mary Shelley’s novel continues to exert a cultural influence that is arguably unmatched by any other work of fiction. We find her “hideous progeny” haunting everything from science fiction to cinema, philosophy, feminist and queer theory, and debates about artificial intelligence. Frankenstein proved to be an unexpectedly incisive and agile intellectual project for an eighteen-year-old girl. It is at once a semi-autobiographical psychodrama, a tale about the limitations of human knowledge, and a keen social commentary of early nineteenth-century Europe.

On the occasion of its bicentennial, The Alcalá Review invites the submission of ghost stories in the spirit of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. As all ghost stories do, the strongest submissions will explore some cultural anxiety or fear that finds expression in a tale of horror and/or the supernatural. Possible topics of exploration include race, sexuality, contemporary politics, science, and media cultures. Whatever the subject, the story must find ways to, as Shelley put it, “awaken thrilling horror” and “quicken the beatings of the heart.” The winning story will be featured in the spring 2019 issue of The Alcalá Review.

Guidelines: Stories must be between 500 and 2500 words

Deadline: February 15, 2019

Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818)

Frontispiece illustration (1831 edition).

Cabaret Voltaire – Alana Hollenbaugh

by Alana Hollenbaugh

Literature is a new language with liquor on my lips his lectures are litanies to Plath, Lewis, and Longfellow.

Sitting beside the bar at the Cabaret Voltaire ignoring the dancers’ swirl

we debate the poetry of the dark downpour outside. He sees celebration: swirling puddles of snowdrop petals

illuminated by soft streetlights.

I disagree, telling him

that it is morning-after rain—

trying to wash the dirt from the night still being lived.

It is muddied and lost: streaming frantically through the gutters.

Silence sits heavy in the separation between our thoughts

The band raps rhymes between us: thuds and beats to our meter.

We wander home through the streets, then

with entangled fingers. His alleys are paved with petrichor—

mine are drizzled in cheap beer.

This poem originally appeared in the Fall 2016 Issue.